[ad_1]

After Brussels, Vienna and Lucerne, the collection of works by David Hockney (more than sixty years of creation) owned by the Tate Modern in London is coming to Aix-en-Provence (Bouches-du-Rhône). The museum has acquired paintings, collectors have made donations and so has the artist, so that this is almost a retrospective (although it lacks the Polaroid collages which are among its most inventive experiments). It is none the less very instructive.

First of all for the policy implemented by the British museum institutions of the Tate, which proceed with Hockney as before with Bacon and Freud: by making the British artist a star and by concentrating on him the essential of their action international. The Aix exhibition is an illustration of this promotional tactic. And its attendance success verifies its effectiveness.

On the name of Hockney, it is possible to bring in winter, excluding tourism and festivals, between one thousand two hundred and one thousand five hundred visitors a day to the Granet Museum and to fill the rooms to the point of sometimes having to prevent them from entering. .

But this process, which confuses history and publicity, has a serious defect: to designate an artist and only one per generation amounts to relegating to the half-light those of his contemporaries who would have been also worthy of this favor. Hockney was promoted to master of British pop art. Doesn’t Richard Hamilton deserve so much consideration? And Peter Blake? Too late. It will be decades before a rebalancing occurs.

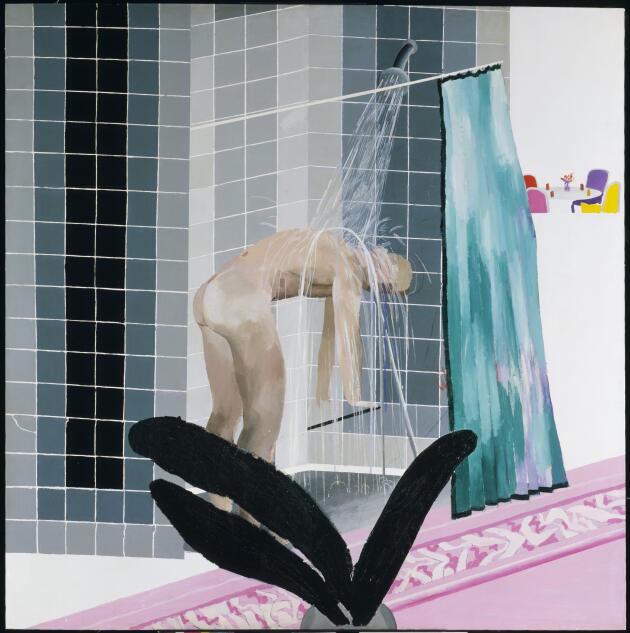

The second interest of the exhibition is that it makes Hockney’s work clearly visible: his increasingly accentuated tendency towards mannerism and self-quotation. On the one hand, there are his first fifteen years, and on the other, what followed.

The former are well represented here: major canvases and suites of drawings and engravings no less major. The following decades are no less, mainly through drawings, lithographs and, at the end, a huge digital composition of 2017 and the works on iPad.

This presentation in shorthand favors comparisons from one era to another. It also shows that Hockney has never ceased to be a practitioner of exceptional dexterity and technical curiosity, both when he was a student at the Royal College of Art and today. But his talents ended up being the heart of his works, as if that were enough.

You have 66.08% of this article left to read. The following is for subscribers only.

[ad_2]