[ad_1]

“Life and Destiny” (Zhizn i Sudba), by Vassili Grossman, translated from Russian by Alexis Berelowitch and Anne Coldefy-Faucard, preface by Luba Jurgenson, Calmann-Lévy, 1,200 p., €31, digital €30.

“For a just cause” (Za pravoye delo), by Vassili Grossman, translated by Luba Jurgenson, Calmann-Lévy, 1,100 p., €31, digital €30.

“Everything passes” (Vso techot…), by Vassili Grossman, translated by Jacqueline Lafond, foreword by Linda Lê, Calmann-Lévy, 300 p., €21.90, digital €16.

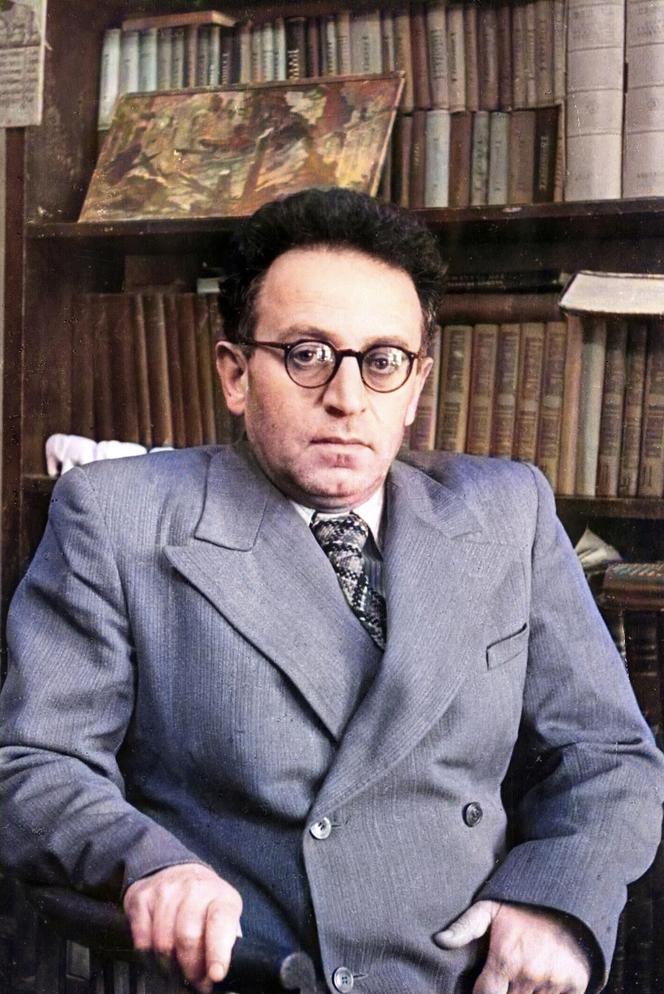

A book that frightened one of the most powerful states in history enough that its police tried to make it simply disappear. A work that testifies to the intrepid struggle of a thought tearing itself away from the beliefs that held it submissive. This book is life and destiny, of which the KGB seized, in 1961, all the typescripts and even the tapes of the machines used to type them, and of which Mikhail Suslov, the chief ideologue of the Soviet Union at the time, said that he could not appear before two hundred years. This work is that of Vasily Grossman (1905-1964), who began his career as a standard Soviet writer and ended with Anything goes, his latest book, by writing a radical indictment not only against the USSR, but against millennial Russia as a tomb of freedom and as an empire. Grossman’s work is a hymn to freedom, and it is itself the heroic act of a freedom in the process of conquering itself.

Whether life and destiny were only the story of the Battle of Stalingrad (July 1942-February 1943), it would be one of the most formidable war stories there is, but that would be it. Now, it is also, and even above all, a story of souls (yes, this Bernanosian word, as is Bernanosian this movement of thinking against its tradition), the chronicle of their weaknesses, their little cowardices, their doubts, their outbursts . What makes it so exciting to read is that this enormous and infinitely delicate book is able to describe both the great scene of the war and the ridiculous vexation of the great physicist who receives from the Party the same food parcel as a nullity scientist, or his childish pride when Stalin, whom he nevertheless knows to be a tyrant, calls him on the telephone (and the irony of these episodes is all the more remarkable since this character is, in the novel, the representative of the ‘author). It is the story of the thousand tricks, often pitiful, that worried, weak souls invent against fear – not fear of the enemy: fear of the Moloch-State.

You have 68.45% of this article left to read. The following is for subscribers only.

[ad_2]