[ad_1]

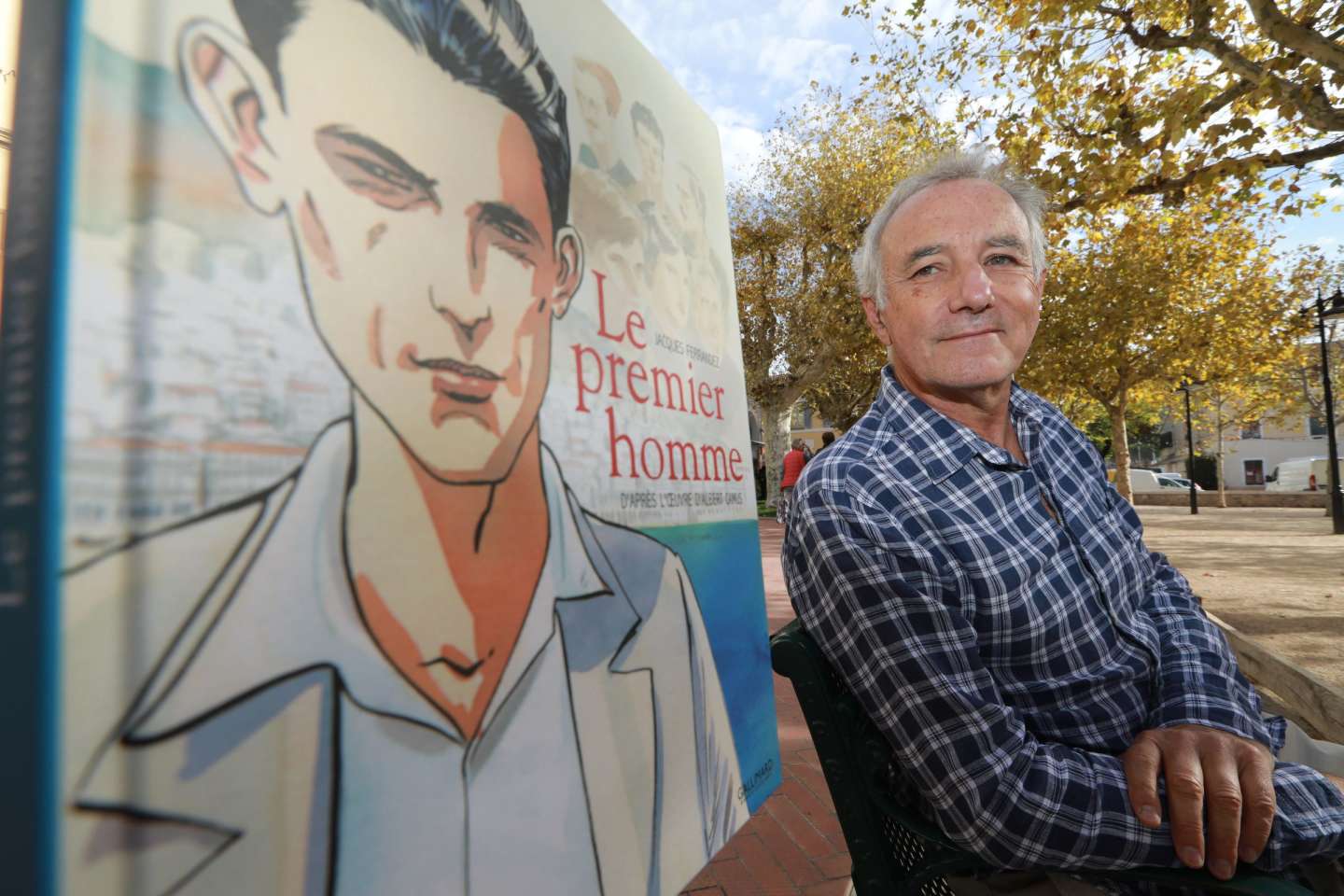

Jacques Ferrandez naturally did not suspect, when publishing his first Oriental Notebooks, in 1987, that he would only complete his Algerian saga thirty-six years later. Born in 1955 in an Algeria that his parents left shortly after, the designer from Nice certainly had an early passion for his native country. But it is the romantic breath of his Algerian fresco that pushed him to first publish a series of five albums on the Algeria of French colonization, then five others on the war of independence. The cycle is now completed by the two volumes of his Algerian Suiteswhich cover the period from 1962 to 2019, the second and last volume having just been released by Casterman.

The series of “Notebooks of the Orient”

Ferrandez opened his Notebooks of the Orient with the discovery of Algeria by a painter with the false allure of Delacroix who, having fallen madly in love with a beautiful Djemilah, crossed the country to find her, not without learning Arabic and becoming Arab himself. The reader followed this Joseph/Youssef from the siege of Constantine, in 1837, to the camp of the Emir Abdelkader, then as much in the fight against the French invader as against the other Arab leaders. Prefaced by Jean-Claude Carrière, Jules Roy, Benjamin Stora and Louis Gardel, the next four volumes of this cycle each focused on a pivotal moment in colonial Algeria: 1871 and the arrival of the communard exiles in the midst of the Kabylie insurrection; the beginning of the XXe century of a childhood between Beni Ounif and Mascara; 1930 and the centenary of the French occupation; and finally 1954 before the start of the armed struggle by the National Liberation Front (FLN).

Ferrandez sincerely thought of stopping there, before embarking, in 2002, on a new cycle of five albums, whose action is marked by the different phases of the Algerian war. By placing himself in a more collected chronology, the author, even if he had already followed characters from one album to another, this time builds a denser saga, with its intrigues, its twists and its secrets. The charm of the scenario and the illustrations is served by rich documentation and solid research, over many stays in Algeria and increasingly trusting relationships with witnesses from all sides.

Not only is success there, but the Oriental notebooks also find their audience in Algeria, in French as well as in a local translation into Arabic. The Algerian daily El Watan salute the ” simply colossal work by Jacques Ferrandez, who “invites us to distrust official history, to look within ourselves, to confront our past with its darker sides”.

You have 44.15% of this article left to read. The following is for subscribers only.

[ad_2]