[ad_1]

“Ghost film”, by Patrice Pluyette, Seuil, “Fiction & Cie”, 236 p., €19, digital €14.

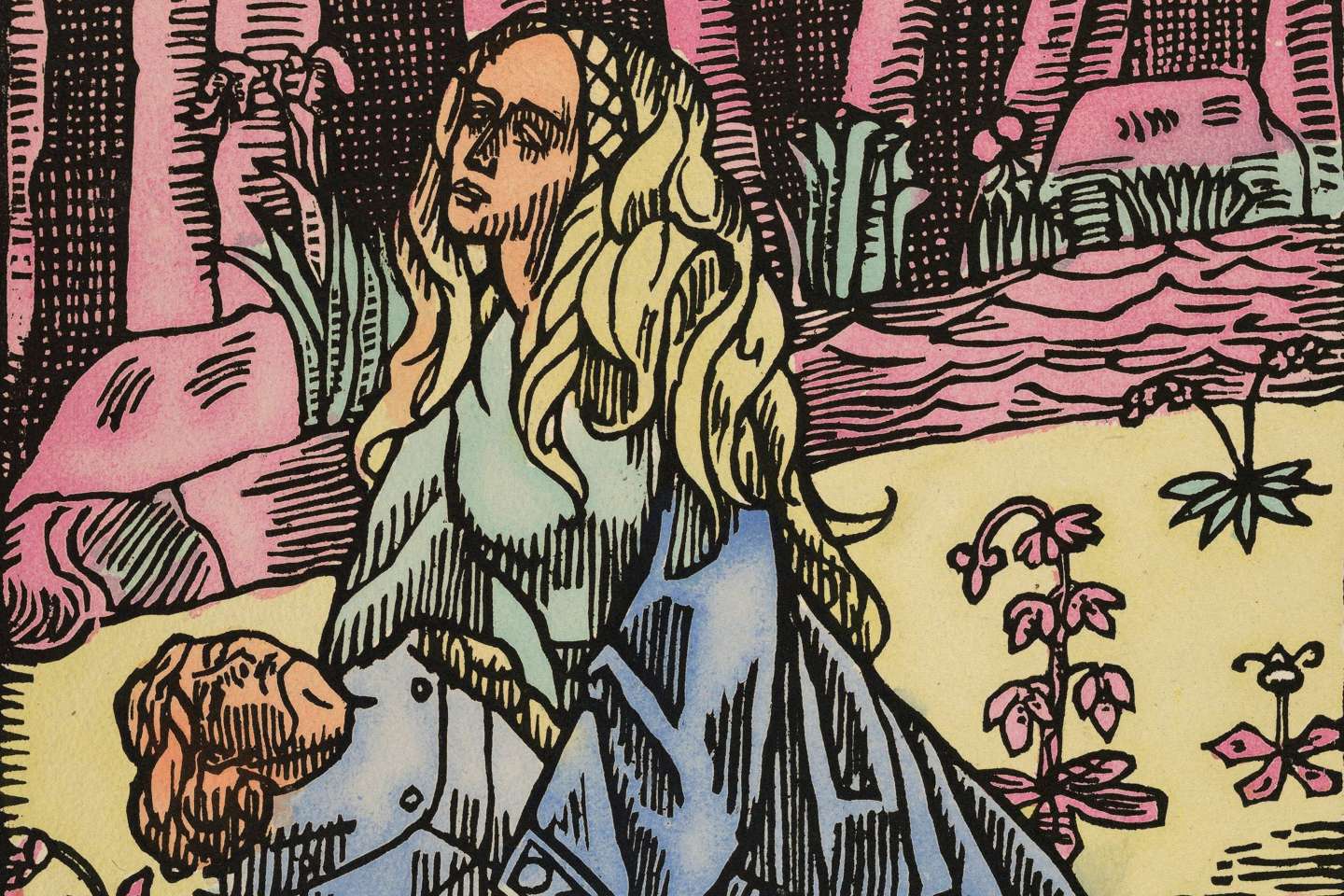

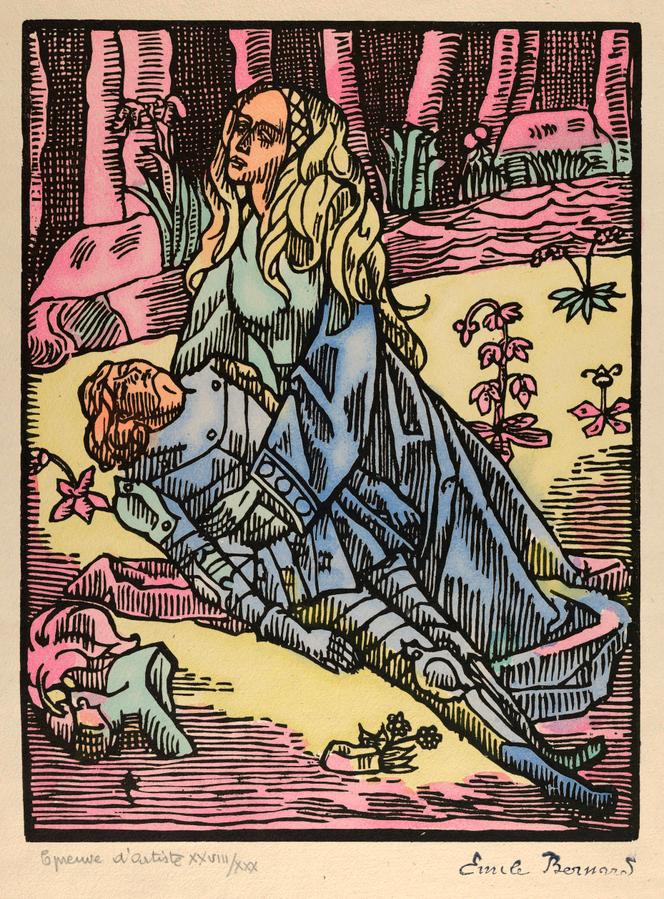

Obviously not out of breath from his trek through literary genres, Patrice Pluyette tackles this time, like a climber embarking on an ascent, to a summit of the story of chivalry, after having surveyed different genres of novels: adventures (Crossing Mozambique in calm weatherThreshold, 2008), libertine (A summer on the Magnificent, Seuil, 2011), detective (The Ant MurdersSeuil, 2015) and naturalist (The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, Threshold, 2018). In ghost moviethe writer entrusts the narration to a colleague without great talent, whose dream is to swap the pen for the camera in order to bring to the screen Orlando furiousof Ariosto, vast and sinuous epic poem of the XVIe century in the heart of which Roland, the nephew of Charlemagne, lived a great heartache.

Protean work

Because of its status as a masterpiece, the Italian text is like an all-you-can-eat buffet from which many painters, playwrights, composers and writers have tried their hand at adapting or rewriting this novel. The incredible plasticity of the work perfectly suits that of Patrice Pluyette’s very protean form. Its narrator, ready to render an unorthodox copy, rubs his hands on it: “Roland is a hero who has become mythological and you can do whatever you want with him, inventing new lives for him, new stories, reusing him to make him evolve at different times. » Go for the craziest scenes, like when Roland “gets a little backflip just for looks (…)followed by a colossal somersault”. Or when the hero is considering a career change: I’m leaving the army, he said to himself. (…), I go into private life, I set up my non-violent self-defense business (he mimics combat gestures). »

Like Roland, yamakasi here, judoka there, the novel has something athletic about it: it’s a series of back and forth between the conception of the project (we’re running towards the masterpiece!) and the shooting complicated (we limp towards the turnip…). Between the intention and the realization, the gap widens – the chaptering also takes care to keep them in separate spaces. And, when the main actor finally reveals himself “not so bad” during filming, the narrator is delighted to finally see the emergence “a character who goes beyond (s)expectations ». What an irony: the budding director mainly desires what is beyond his desires.

Defeat a fly!

You have 30.71% of this article left to read. The following is for subscribers only.

[ad_2]