[ad_1]

The scene looks like a tableau vivant. In front of us, two young women are combing huge statues with black threads. Using a small wooden stick, they silently untangle braids, cords and tiny vines that look like hair. The gesture is repeated, soft and precise, as in a hypnotic trance. In a few days, three works by visual artist and researcher Jeanne Vicérial will be presented as part of a collective exhibition, called “Beyond. Rituals for a new world”, at Lafayette Anticipations, the exhibition space of the Galeries Lafayette Foundation located in the Marais, in Paris.

For the time being, it is a question of putting in folds these sculptures from beyond the grave: two “Armor” giant textiles, “disturbing warriors made of love as much as armor” straight out of mythology, and a “recumbent” on his tomb, a sort of sacred phantom with entrails pierced with a heart of dried peonies. Then, these mysterious female figures will be perfumed with scents imagined by Jeanne Vicérial, “perfume of objects” elaborated in collaboration with the nose Nicolas Beaulieu.

“I was becoming more and more uncomfortable with the idea of putting new clothes on the market when we have enough for the next hundred years. » Jeanne Vicerial

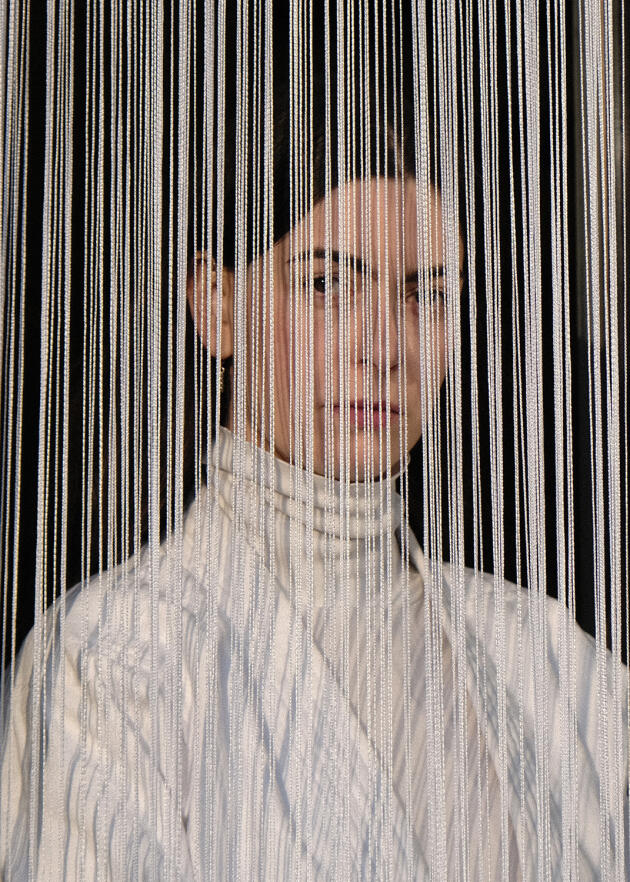

Once this preparation phase is complete, the works can be unveiled to the public. “I discovered in the world of art a freedom that I never found in fashion”, explains the 31-year-old visual artist, who left fashion design to branch off into the art world. She has been represented for a year by the Templon gallery, where fifteen of her clothing sculptures are exhibited until March 11. The opportunity to see that the designer handles immaculate white as well as jet black.

After studying costume design and then a master’s degree in clothing design from the School of Decorative Arts in Paris in 2015, Jeanne Vicérial joined the studio of stylist Hussein Chalayan. “I tried fashion competitions without success, I wanted to launch my ready-to-wear brand, but I never managed to find my place in this industry”, she said without regret. A bad for a good. “It just wasn’t the right environment for me. And then, I became more and more uncomfortable with the idea of putting new clothes on the market when we have enough for the next hundred years. Today, I no longer have any desire to enroll in a process of mass production. »

You have 76.13% of this article left to read. The following is for subscribers only.

[ad_2]